|

Barry Bogs--The Gauge 3 Steam Locomotives

|

Barry Bogs is a prolific model builder residing in the

Houston, Texas area, whose work has appeared several times

over in

Model Railroader,

Garden Railways,

Finescale Railroader, and the LGB

Telegraph. In real life Barry is a technician for

Pitney-Bowes; but in his off time, He models the Denver &

Rio Grande Western in 1:22.5 scale, with both standard gauge

and narrow gauge operations, much like the prototype. Barry

uses Gauge 3 (2.5" between the rails) to represent 4'-8½"

standard gauge and Gauge 1 to represent 3' narrow

gauge (what some are dubbing G and Gn3).

Barry's large scale indoor railroad, the

Colorado & Western, is

now in its second incarnation and covers nearly the entire

second floor, including the open foyer, of his substantial

home. But aside from Barry's layout being itself visually

stunning (as it tunnels through walls and crosses hallways

via lift-out bridges), his most impressive talent is his

scratchbuilt locomotives and

rolling stock. Only Barry's

standard gauge steam is presented here,

diesels here. Please see the

Colorado & Western site

for pics of Barry's layout and his stable of D&RGW narrow

gauge locomotives. Barry may be contacted at

blbogs@yahoo.com

|

Barry & Gauge 3--An Apology of

Sorts

Although Barry is not modeling in 1:20.3 standard

gauge (he has far too large an investment in 1:22.5 scale to even

think of switching), his work warrants a page on this website because (1) the Gauge 3 models he

builds are themselves very close in size and concept to 1:20.3

standard gauge, (2) the

techniques he uses are readily adaptable to standard gauge modeling

in 1:20.3, (3) he has completed a number of my former Gauge 3 projects, (3) he's

my friend, and (4) in some small measure I am responsible for getting

him started in Gauge 3. Perhaps a personal anecdote to that effect is in order

here.

Barry and I first met sometime in the early 90s while

I was still in seminary, unmarried, and just beginning to dabble in

Gauge 3. As has often been the case in the world of large scale,

Marc Horovitz was the facilitator who introduced Barry to myself,

having related to him that at least one other person was fiddling

with two rail electric models in Gauge 3 but residing nearly a 1000

miles away in east Tennessee. Sometime after that, Barry visited me

between semesters at my parents home in

Knoxville where I had set up a workshop with a 24' long shelf

layout for testing

purposes. Those two

tracks, with their #8 crossover, the as-of-then incomplete

Canadia City Boxcar and

40' basswood

flat, were probably the first Gauge 3 models Barry had seen

in person, though he had seen photos of the hard-to-find

Magnus products. He was hooked.

Several years after this, Barry visited again, and I was able to

place a handful of custom-made Gauge 3 axles in his hands. Since

that time, he has adopted three of my Gauge 3 flat cars, completed an

orphaned 2-bay hopper, transformed a box of disparate parts into a

beautiful 2-4-4-2 mallet, built his own fleet of standard gauge

freight cars, and constructed the largest indoor dual gauge layout

in 1:22.5 scale in the country. Given his accomplishments, I'm now convinced either

Barry does not sleep, does not really have a day job and is in fact

independently wealthy, has a twin brother who also likes trains, or

perhaps some combination of all three. Whatever the case, you may

judge for yourself below.

Tools & Techniques

.gif) Barry builds

his locomotives and rolling stock from a combination of styrene

plastic, urethane castings (made from his own styrene patterns), metal

detail parts, and where locomotives are concerned, LGB motor blocks

and wheelsets, regauged if necessary to Gauge 3. He is able to work

with incredible speed from--now get this--a roll top desk in his

family room! The actual urethane casting process, as well as the

painting of his models, is done in a non-air-conditioned garage (in

stiflingly hot and humid Houston) and out-of-doors, respectively. Barry builds

his locomotives and rolling stock from a combination of styrene

plastic, urethane castings (made from his own styrene patterns), metal

detail parts, and where locomotives are concerned, LGB motor blocks

and wheelsets, regauged if necessary to Gauge 3. He is able to work

with incredible speed from--now get this--a roll top desk in his

family room! The actual urethane casting process, as well as the

painting of his models, is done in a non-air-conditioned garage (in

stiflingly hot and humid Houston) and out-of-doors, respectively.

Because Barry's models are meant to run, and to run

reliably, they are constructed somewhere between museum quality and

semi-scale. For instance, since LGB provides the running gear almost

exclusively, a given steam locomotive wheelbase may be off by a few

scale inches, and Barry's typical wheelset is LGB off-the-shelf

with its tinplate style high flanges (but most visitors, at least

the polite ones, are not measuring his locomotives with a set of

dial calipers). Likewise, brake rigging mounted beneath a car or

locomotive is rarely duplicated because it is almost never seen and,

well, gets torn off with very much use or handling. Those items for

which no commercial parts are available (domes, cabs and such) Barry

scratch- builds, and

these parts do scale out on the money. Rivets for

instance follow the pattern of prototype drawings and number in the

hundreds for any given tender or freight car. What Barry has done,

then, is to achieve a workable balance between reliable operation

and proportional good looks.

Since LGB

does not offer a plastic, Gauge 3 steam locomotive, Barry has had to

go beyond the techniques of the typical kitbasher to arrive at

something a little more radical, while still making use of a

commercially available drive. The result is what might best be

described as motor block sandwich. Simply put, an LGB

motor block, with either its own or more likely after-market drivers

of an appropriate OD, is regauged using new 6mm axles. A new styrene

frame to match that of the prototype locomotive is cut out, spacers

between it and the motor block are also cut, and the whole assembly

is glued and screwed together. No new axle bearings are provided for in

the sandwich; rather, the original motor block's own bearing surfaces

suffice. New cylinders, engine truck frames, and such are then

fabricated out of styrene and PVC tube and attached to the new

styrene frame. Generally, there is no working suspension: All leaf

springs, equalizers & levers are entirely aesthetic. Since LGB

does not offer a plastic, Gauge 3 steam locomotive, Barry has had to

go beyond the techniques of the typical kitbasher to arrive at

something a little more radical, while still making use of a

commercially available drive. The result is what might best be

described as motor block sandwich. Simply put, an LGB

motor block, with either its own or more likely after-market drivers

of an appropriate OD, is regauged using new 6mm axles. A new styrene

frame to match that of the prototype locomotive is cut out, spacers

between it and the motor block are also cut, and the whole assembly

is glued and screwed together. No new axle bearings are provided for in

the sandwich; rather, the original motor block's own bearing surfaces

suffice. New cylinders, engine truck frames, and such are then

fabricated out of styrene and PVC tube and attached to the new

styrene frame. Generally, there is no working suspension: All leaf

springs, equalizers & levers are entirely aesthetic.

On some locomotives, such as Barry's first Gauge 3

mallet (a Denver & Salt Lake 2-6-6-0) a three axle LGB motor block

was used and the same sandwiching technique carried out. On an

eight-coupled locomotive, such as Barry's D&RGW L-131 2-8-8-2 simple

articulated (now on the workbench) or his C-41 2-8-0, the relatively new LGB Mikado

motor block (which is actually engineered as a 2-4-4-2, having a

hinge between the #2 and #3 drivers) can be adapted just as readily.

The only limitation with the LGB motor blocks is (1)

wheelbase--unless one is willing to cut the motor blocks themselves

apart, change the placement of motors and gears as needed, and

re-glue the assembly together) and (2) driver OD. So far the largest

LGB driver readily available is that of the Mikado which measures

about 43" in 1:20.3 across the tread; the Mikado's wheelbase being

about 51" between the drivers as well. |

|

The Locomotives

Denver

& Salt Lake 2-6-6-0 Denver

& Salt Lake 2-6-6-0

(2004)

Built in 1916 by Alco's Schenectady

works for the Denver & Salt Lake, a line absorbed into the Denver &

Rio Grande Western in 1947, these 2-6-6-0 mallet compounds had 55"

drivers and exerted about 77,000 pounds tractive effort (hence the

D&RGW's designation L77). They were short lived on the

D&RGW, all of the class having been dismantled by mid 1952.

Barry's model of this unusual class of

mallet was intended mainly to demonstrate the startling difference

between a mid-size standard gauge mallet and the largest of 3'

narrow gauge equipment: the D&RGW outside frame K-37 2-8-2. It is

his first Gauge 3 locomotive, and his favorite so far. #3375 was

constructed with the help of an O scale

brass model imported by Pacific Fast Mail (PFM) and a handful of scale drawings provided by

the same. No readily available D&RGW or D&SL blueprints for this locomotive are

known to exist. |

|

The Tender

The tender body, shown below, was made

from .060" styrene sheet, which was then wrapped in .010" sheet (in

order to mask the rounded corners made from sectioned lengths of PVC

pipe). Peco track nails were then applied to simulate rivets. The

tender underframe is made from Plastruct channels, and the whole

affair rides on cast urethane Andrews style tender trucks. LGB

plunger type wipers are used for power pickup. The trucks are rigid

since the high LGB tinplate flanges assure reliable operation on

undulating track.

|

|

The Chassis, Boiler & Cab

Barry used two LGB Mogul motor blocks

for the #3375's drive, each regauged with new 6mm stainless steel

Gauge 3 axles and reequipped with LGB Mikado drivers (which were

themselves modified with new counterweights). The main frames

sandwiching the motor blocks are .250" thick Evergreen styrene

plastic strip. Similarly the tender and cab are made from .060"

styrene sheet. The boiler is a length of 4" OD Plastruct tube.

Cylinders and domes were fabricated whereas the stack was cast in

urethane from a styrene pattern. Three couplers are mounted to both

pilot and tender so as to facilitate dual gauge operation. The

locomotive is able to negotiate a 5' minimum radius curve.

|

|

The Completed Locomotive

|

|

.jpg) Little River Railroad 2-4-4-2 Little River Railroad 2-4-4-2

(2005)

In the late Spring of 2005 Barry

visited my workshop here in East Tennessee where we discussed our

current and past projects. One of my past projects, from the Gauge 3

phase of my sojourn in large scale, was a series of Little River

Railroad logging mallets, each based upon the first of the Little

River's two mallets: #126 (The story of that project can be read

here,

_small.jpg) _small.jpg) near

the bottom of the page). Barry left that evening with all the

remaining parts I had on hand for the 2nd of

what would have been four locomotives, which included regauged

Palacina Productions drivers, spoked lead & trailing truck wheels

(adapted from an LGB electric locomotive), the tender underframe, an incomplete tender body,

Barry's own K-37 archbar tender truck castings, a couple of LGB 0-4-0 motor blocks, a

brass smokestack, a bag of commercially available detail

parts--including custom made builders and number plates by Robert

Dustin--and photo copies of all the dimensioned drawings and

research I had been able to accumulate for Little River#126, better

known on the West Coast, and to the present day--since the locomotive still exists, albeit in pieces--by its Native American

name, the Skookum. near

the bottom of the page). Barry left that evening with all the

remaining parts I had on hand for the 2nd of

what would have been four locomotives, which included regauged

Palacina Productions drivers, spoked lead & trailing truck wheels

(adapted from an LGB electric locomotive), the tender underframe, an incomplete tender body,

Barry's own K-37 archbar tender truck castings, a couple of LGB 0-4-0 motor blocks, a

brass smokestack, a bag of commercially available detail

parts--including custom made builders and number plates by Robert

Dustin--and photo copies of all the dimensioned drawings and

research I had been able to accumulate for Little River#126, better

known on the West Coast, and to the present day--since the locomotive still exists, albeit in pieces--by its Native American

name, the Skookum.

|

|

The

Tender The

Tender

Barry picked up the baton where I had dropped it by first working on

the tender, in typical Barry Bogs fashion: Build the tender first,

so that if one grows weary of the project, he will not sputter near

the finish line with a nearly complete locomotive but no tender. For

those of you who would like to follow along and learn his techniques,

Barry has provided a written narrative of the tender's construction:

Part I: The Trucks The

first thing that I build is the tender trucks. If you can find some

ready made side frames that will work for your engine, it will save

time. Luckily, Little River 2-4-4-2 #126 used the same tender truck

side frames as those on the D&RGW K-37 for which I had already made

patterns and molds. When I pour casting resin into my molds, I drop

preformed steel rod into the mold. This gives the casting strength,

like steel rods do in concrete. I sand off the back side of the

casting and drill holes into it to accept plastic tube with an

⅛” ID hole. This will be the

journal bearing that the axle

will ride in. Small roller bearings are available, which would work

for high use situations, but styrene bearings have been sufficient for

all my locomotives.

On these particular trucks, I used LGB metal wheel sets, with

3mm axles, which I regauged for Gauge 3 using new 3mm steel rod

from Northwest

Short Line along with a spacer tube to go between the LGB

axle tubes.

Plastruct

¼" X 9/16" rectangular stock is used for bolster material. I super

glue (ACC is my adhesive of choice) the Plastruct bolster to one

side frame and then glue a separate block to the opposite side

frame. Using LGB screws, I then screw the assembly together on one

side to make

a rolling truck. Wheel sets are replaceable by disassembling one

side frame from the bolster. Plastruct

¼" X 9/16" rectangular stock is used for bolster material. I super

glue (ACC is my adhesive of choice) the Plastruct bolster to one

side frame and then glue a separate block to the opposite side

frame. Using LGB screws, I then screw the assembly together on one

side to make

a rolling truck. Wheel sets are replaceable by disassembling one

side frame from the bolster.

Since I use track power,

electrical pickup is via bolster mounted wheel wipers; and here, I use LGB

plunger style pickups.

For Gauge 3, I added additional mounting blocks to the bolster and

cut the LGB wiper holders in half. I then insert the brushes into

the holders and screw the holders to the mounting blocks. I wire them after

everything is built.

Ozark Miniatures brake shoes were

then mounted to

plastic strip and glued to the bolster.

Trackside Details

makes chain mounting eyelets that I mount to the top corners of the side

frames. I drill a 17/64” hole in the center of the bolster that a

¼” tube can go through. The trucks are done for now.

Part

II: The Tender Deck I usually build the tender deck using

plastic for the structure and metal castings for the details.

Since Dave Queener started this project, I decided to use the basic deck

that he had made. Dave made the frame rails out of styrene channels with wood

end beams and a wooden deck. Dave then added two 2-56 threaded rods

running the length of

the deck to make sure the end beams could not be pulled apart. The real wood looks good on this tender.

I usually make my end beams out of large plastic strips and drag a coarse

Zona saw across them to give the look of wood.

Likewise, the deck is usually a sandwich of 0.040"

Evergreen scribed siding (with

¼" spacing) with

another sheet on top aligned to the scribes on the bottom. I drag

the Zona saw across both top and bottom sheets to make them look like wood. Part

II: The Tender Deck I usually build the tender deck using

plastic for the structure and metal castings for the details.

Since Dave Queener started this project, I decided to use the basic deck

that he had made. Dave made the frame rails out of styrene channels with wood

end beams and a wooden deck. Dave then added two 2-56 threaded rods

running the length of

the deck to make sure the end beams could not be pulled apart. The real wood looks good on this tender.

I usually make my end beams out of large plastic strips and drag a coarse

Zona saw across them to give the look of wood.

Likewise, the deck is usually a sandwich of 0.040"

Evergreen scribed siding (with

¼" spacing) with

another sheet on top aligned to the scribes on the bottom. I drag

the Zona saw across both top and bottom sheets to make them look like wood.

With the basic deck done, it is time to make

some decisions. Most plans and O scale models have very little or no

under deck details. The O scale model I examined for this engine was no exception.

In cases like this, the best thing to

do is to take some pictures of a prototype tender about the same size or find

another O scale model that has underbody details. I looked at a

brass D&RGW K37 in On3

for some clues. What you see on the

completed deck is what I came up with. The underframe braces, for

instance, are cut from

plastic strip and glued on. The next step is to measure the height of the

top of the deck to the top of the rail on the plan. I slide the

completed trucks under the new deck and start filling the space

between the top of the truck bolsters and the frame rails of the

deck with plastic strip, until I get the deck height correct. Once

you find the correct thickness, cut and glue the strips to the frame

rails the right length from the ends of the deck, according to the

plan. With the basic deck done, it is time to make

some decisions. Most plans and O scale models have very little or no

under deck details. The O scale model I examined for this engine was no exception.

In cases like this, the best thing to

do is to take some pictures of a prototype tender about the same size or find

another O scale model that has underbody details. I looked at a

brass D&RGW K37 in On3

for some clues. What you see on the

completed deck is what I came up with. The underframe braces, for

instance, are cut from

plastic strip and glued on. The next step is to measure the height of the

top of the deck to the top of the rail on the plan. I slide the

completed trucks under the new deck and start filling the space

between the top of the truck bolsters and the frame rails of the

deck with plastic strip, until I get the deck height correct. Once

you find the correct thickness, cut and glue the strips to the frame

rails the right length from the ends of the deck, according to the

plan.

I use a

¼" tube or rod to make the pivot

point for the trucks. Drill through the center point of the plastic

body bolster and through the deck, if it is plastic, to make sure the pivot

rod is secured when glued in place. Glue the tube or rod in place

and slip the truck over it. Mark the rod or tube about 1/16” above

the truck bolster and take the truck off. Cut it at the mark and

drill a small pilot hole for a screw and washer to hold the truck

on. In addition, a metal ¼” rod is used for the draw bar pin on

this model. To secure it, I use plastic block and strips glued to the inside frame

rails, dilled to accept the rod. I use a

¼" tube or rod to make the pivot

point for the trucks. Drill through the center point of the plastic

body bolster and through the deck, if it is plastic, to make sure the pivot

rod is secured when glued in place. Glue the tube or rod in place

and slip the truck over it. Mark the rod or tube about 1/16” above

the truck bolster and take the truck off. Cut it at the mark and

drill a small pilot hole for a screw and washer to hold the truck

on. In addition, a metal ¼” rod is used for the draw bar pin on

this model. To secure it, I use plastic block and strips glued to the inside frame

rails, dilled to accept the rod.

Once

the trucks are on, add all the piping and detail parts to the deck,

according to the plan. With the bottom done, mark and drill for the

rivet detail on the side rails. I use a #74 drill bit and

Peco track fixing pins cut to about

⅛” long,

for rivets. These are used on all other areas of the engine that

call for rivet detail. With the rivets on, add all remaining details

such as steps and buffers. I mounted a

Kadee

"G" scale end beam coupler pocket

and knuckle to this model, because it will be a logging engine. On most

on my narrow gauge engines, I truck mount the coupler, to better

couple and uncouple on tight curves. Body-mounted or truck-mounted:

It's your choice. Finally, I added brass steps and cut levers to the

rear of the tender deck. I drill the deck for both speaker holes and

wiring once the tender is done. With the deck finished and

rolling, it’s time to start on the tender tank. Once

the trucks are on, add all the piping and detail parts to the deck,

according to the plan. With the bottom done, mark and drill for the

rivet detail on the side rails. I use a #74 drill bit and

Peco track fixing pins cut to about

⅛” long,

for rivets. These are used on all other areas of the engine that

call for rivet detail. With the rivets on, add all remaining details

such as steps and buffers. I mounted a

Kadee

"G" scale end beam coupler pocket

and knuckle to this model, because it will be a logging engine. On most

on my narrow gauge engines, I truck mount the coupler, to better

couple and uncouple on tight curves. Body-mounted or truck-mounted:

It's your choice. Finally, I added brass steps and cut levers to the

rear of the tender deck. I drill the deck for both speaker holes and

wiring once the tender is done. With the deck finished and

rolling, it’s time to start on the tender tank.

Part III: The

Tender Tank Now that the deck is done, the tank can

begin. I design my tender tanks to be light weight, but strong. The

basic design is a 0.060" sheet plastic box, with a 0.010" plastic

wrapper. The reason for using 0.060" plastic is that Plastruct tube

has the same wall thickness. The structure of the tender tank is

made using this 0.060" styrene mated to quartered pieces of

Plastruct tube on the "corners" of the tank. Start with your scale

drawing. If you have a top

view of the tender, match the curved sides of the tank with the

correct diameter of Plastruct tube. The next task is to cut the tube

to length. Mark a straight line along the side of the tube next. To

do this, I lay it in a mini miter box and draw a line in ink with a

Sharpie pen using the top edge of the box as my guide. I measure the circumference of the tube next

and divide it in half or quarters, depending on the need. A fine

tooth razor or Zona saw is then used to cut the lines drawn. Hold the

tube in a vice while you cut it. Clean the edges, and it’s ready to

glue to the sides. Cut out the tank side and end profiles from the

0.060" plastic sheet. Glue the corners with a butt joint, using

super glue or ACC. Use a small square to make sure the box is

square. Part III: The

Tender Tank Now that the deck is done, the tank can

begin. I design my tender tanks to be light weight, but strong. The

basic design is a 0.060" sheet plastic box, with a 0.010" plastic

wrapper. The reason for using 0.060" plastic is that Plastruct tube

has the same wall thickness. The structure of the tender tank is

made using this 0.060" styrene mated to quartered pieces of

Plastruct tube on the "corners" of the tank. Start with your scale

drawing. If you have a top

view of the tender, match the curved sides of the tank with the

correct diameter of Plastruct tube. The next task is to cut the tube

to length. Mark a straight line along the side of the tube next. To

do this, I lay it in a mini miter box and draw a line in ink with a

Sharpie pen using the top edge of the box as my guide. I measure the circumference of the tube next

and divide it in half or quarters, depending on the need. A fine

tooth razor or Zona saw is then used to cut the lines drawn. Hold the

tube in a vice while you cut it. Clean the edges, and it’s ready to

glue to the sides. Cut out the tank side and end profiles from the

0.060" plastic sheet. Glue the corners with a butt joint, using

super glue or ACC. Use a small square to make sure the box is

square.

I use ACC kicker to speed the setting of the

joints. Be careful with the tank, as the super glued joint is all that is

holding it together. Using more sheet plastic, I make a piece to go

across the inside width of the tank, behind the coal door area. Glue

it to the inside of both sides, and the front water legs of the

tank. This one piece will stiffen up the tank to handle it. I prefer

not to make the deep coal area of the tank. Instead, I put a full

sheet of plastic across the area, all the way to the back end of the

tank. I file the corners to fit the rear curves and glue it in place

at the correct height from the top edge of the tank walls. ACC it

from the bottom so the glue joint will not show. With this joint

made, the tank will be much stiffer and you will have the basic tank

done. ⅜" angle Plastruct pieces are

glued to the inside bottom edge of the tank. This makes the bottom

of the sides rigid. I then glue about an inch wide strip, the

inside width of the tank, up on top of the angles, at each end.

These pieces tie the side angles with the end angle and make the

tank even stronger. With this step done, it is time to add the coal

doors and additional structure around the area. I use ACC kicker to speed the setting of the

joints. Be careful with the tank, as the super glued joint is all that is

holding it together. Using more sheet plastic, I make a piece to go

across the inside width of the tank, behind the coal door area. Glue

it to the inside of both sides, and the front water legs of the

tank. This one piece will stiffen up the tank to handle it. I prefer

not to make the deep coal area of the tank. Instead, I put a full

sheet of plastic across the area, all the way to the back end of the

tank. I file the corners to fit the rear curves and glue it in place

at the correct height from the top edge of the tank walls. ACC it

from the bottom so the glue joint will not show. With this joint

made, the tank will be much stiffer and you will have the basic tank

done. ⅜" angle Plastruct pieces are

glued to the inside bottom edge of the tank. This makes the bottom

of the sides rigid. I then glue about an inch wide strip, the

inside width of the tank, up on top of the angles, at each end.

These pieces tie the side angles with the end angle and make the

tank even stronger. With this step done, it is time to add the coal

doors and additional structure around the area.

You now have the shape of the tender, but it

has joints showing. I file the joints down to make sure they are

smooth with either sandpaper or a file. Now is the time to make sure that

the tank is correct to the plan and that no revisions need to be made. I

test fit it to the deck and check to make sure it sits squarely in

place. The next step is to apply the 0.010 " plastic wrapper. I

cut out a piece of sheet plastic that is about an inch wider than

the top and bottom of the sides of the tank. The length of the

wrapper should be from the coal doors, around the sides, to the

middle of the back of the tank. Starting at the coal door area, glue the edge

of the 0.010" sheet next to the door area. Make sure that when it

is glued, the rest of the sheet will cover the side and end. Now put

ACC on the entire area of the water leg, around the front to the

first joint with the side. Lay the 0.010" plastic sheet down and

pull it around the front of the water leg to the side joint. Make

sure that it is flat with no buckles in the plastic sheet. Hold the

sheet until the glue sets. Be careful not to kink the thin 0.010"

sheet, as it could break. I had to fix a crack on one of my water

legs, because the sheet was creased before I used it." You now have the shape of the tender, but it

has joints showing. I file the joints down to make sure they are

smooth with either sandpaper or a file. Now is the time to make sure that

the tank is correct to the plan and that no revisions need to be made. I

test fit it to the deck and check to make sure it sits squarely in

place. The next step is to apply the 0.010 " plastic wrapper. I

cut out a piece of sheet plastic that is about an inch wider than

the top and bottom of the sides of the tank. The length of the

wrapper should be from the coal doors, around the sides, to the

middle of the back of the tank. Starting at the coal door area, glue the edge

of the 0.010" sheet next to the door area. Make sure that when it

is glued, the rest of the sheet will cover the side and end. Now put

ACC on the entire area of the water leg, around the front to the

first joint with the side. Lay the 0.010" plastic sheet down and

pull it around the front of the water leg to the side joint. Make

sure that it is flat with no buckles in the plastic sheet. Hold the

sheet until the glue sets. Be careful not to kink the thin 0.010"

sheet, as it could break. I had to fix a crack on one of my water

legs, because the sheet was creased before I used it."

Barry's

narrative ends at this point, but the remaining work chiefly

concerns adding rivet detail to the tender body, beading to the

edges of the tank's sides, and various detail parts. The end result

speaks for itself.

_small.JPG)

|

|

The Chassis, Boiler &

Cab The

remainder of Barry's 2-4-4-2 was built in typical Bogsian fashion:

LGB motor blocks sandwiched by new styrene frames, side and main

rods adapted from other LGB locomotives (in this case from both the

Stainz 0-4-0 and the Mikado). The boiler itself is Plastruct tube.

The cast urethane domes are Barry's own creations. The usual

complement of

Ozark Miniatures,

Trackside Details,

and

Precision Scale detail parts round out this outstanding

model. Now where can I get mine--in 1:20.3 Standard Gauge?

_small.JPG)

_small.JPG)

|

|

The Completed Locomotive

_small.JPG)

_small.JPG)

_small.JPG) _small.JPG)

_small.JPG)

_small.JPG)

|

|

.jpg) D&RGW

C-41 2-8-0 D&RGW

C-41 2-8-0

(2007)

Built in 1902 by Baldwin, the D&RGW C-41 was a heavy consolidation

for its time, exerting 40,893 lbs. of tractive effort from its 55"

drivers. Overall dimensions, with tender, were 63'-3" long, 10'-2"

wide and 15'-1" tall (track to stack). Each tender carried 9 tons of

coal and 6000 gallons of water. Stephenson valve gear and slide

valve cylinders were original equipment on these locomotives;

however with the advent of superheaters, many of the C-41s were

rebuilt with piston valves and at least two locomotives (#1022 and

#1024) were refitted with Walschaert's valve gear. Over time some of

these engines even acquired Vanderbilt tenders, much like their

larger 1916 vintage 2-10-2 cousins on the D&RGW.

The C-41's single

claim to fame lies in the 1930 conversion of ten of this class to

D&RGW K-37 narrow gauge 2-8-2s, each "new" K-37 receiving the

rectangular tender, archbar tender trucks, boiler, domes & cab of

its C-41 predecessor. New running gear--outside frames, 44" drivers,

piston valve cylinders, outside bearing lead & trailing trucks, rods

and such--were provided by Baldwin. Tender trucks were simply

regauged, retaining their standard gauge bolsters while pressing

new, smaller

wheels several inches closer together on otherwise standard

gauge axles. Most likely new

smoke boxes, petticoat pipes and stacks were applied, as was a new cab

apparently patterned after those on the K-36, and hence, a bit

shorter and more narrow than the C-41 original. In any case, none of the other twenty unconverted C-41s

escaped the scrapper's torch; and to the best that Barry and I have

been able to determine, no D&RGW drawings of the C-41 have survived

either. If anyone is aware of either blueprints of these locomotives or

pictures of the 1930 conversion, please drop

me a note. |

|

The Tender

Having built many a boxy conventional

tender in the past, Barry chose to do something a bit different for

the C-41, choosing locomotive #1022

(pictured above) as his prototype.

This is the first Vanderbilt tender he has done; but much like the

prototype, it rides upon the very same archbar trucks as used on the

K-37, Barry having built several of these over the past number of

years. Aside from styrene, Trackside Details parts, and the usual

combination of regauged LGB wheelsets, the tender is essentially a

3" OD length of ABS tube from Plastruct, complete with end cap. Now

that Barry has shown the way, let's see somebody build one of these

in F scale!

|

|

The Chassis, Boiler &

Cab

Barry's main

interest in building the C-41 is to show what the K-37 predecessor

looked like--a first in any scale to the best of our knowledge. The

irony is that the construction of the model was the reverse process

regarding the construction of the prototype: Barry began with narrow

gauge components and regauged them to standard gauge! For instance,

aside from the regauged K-37 tender trucks, the running gear for

Barry's 2-8-0 is a Gauge 1, LGB Mikado drive unit. The LGB Mikado

drivers were retained, with changes to the counterweights, but

regauged using new 6mm stainless steel axles. A regauged LGB Gauge 1

wheelset was also used for the lead truck. Walschaerts valve gear

from the LGB Mikado was retained, although several pieces were

replaced with Barry's own castings to more accurately represent

those of the C-41. The boiler is, once again, Plastruct; the domes

and stack are urethane castings from Barry's considerable store of

patterns. The engine has been equipped with a Digitrax DCC decoder

and Phoenix 2K2 sound. It

is capable of negotiating 5' radius curves, the minimum on the Gauge

3 portion of Barry's layout,

and

with its Vanderbilt

tender, measures 33.8" long.

Barry writes in

one of his mid-construction updates: "This week's work on the engine

amounts to cab and backhead details. The cab is so time consuming

because of all the rivets on it. There are more rivets on the

engine, than on the tender! I used dimensions off the D&RGW C-48

2-8-0 for the cab's size, as it is so far off from the K-37. The

back head is just a guess, and a poor one at that, so don't look

real close. I am hoping to come up with an article on the C-41 and

K-37, comparing them side by side, to see how different they really

are. I never understood why the model brass importers did not build

a C-41 and K-37 at the same time and release them together; but now

that I have built them, I have found so much that is dissimilar, it

would not have made sense."

|

|

The Completed Locomotive

During

the second week of September 2007, Barry painted and lettered the

C-41. He writes about this final phase of the project: "I

really like the Vanderbilt tender on this engine, as it it is

something different. I also used a crew from

Woodland Scenics for this engine, instead of the same old

guys as are in my other engines. The Woodland Scenics guys are

already painted, so I guess it was instant gratification for me, if

there is such a thing. The sound system is still mounted in the

tender, but the speaker is in the firebox of the engine. Sounds good

to me". During

the second week of September 2007, Barry painted and lettered the

C-41. He writes about this final phase of the project: "I

really like the Vanderbilt tender on this engine, as it it is

something different. I also used a crew from

Woodland Scenics for this engine, instead of the same old

guys as are in my other engines. The Woodland Scenics guys are

already painted, so I guess it was instant gratification for me, if

there is such a thing. The sound system is still mounted in the

tender, but the speaker is in the firebox of the engine. Sounds good

to me".

Barry also took a

series of shots comparing the C-41 to his model of the C-41's narrow

gauge successor, the D&RGW's K-37 2-8-2. Barry remarks about the

differences between the C-41 and the K-37:

As

most of you know, the K-37 NG engines were built from the C-41

SG engines by the Grande in 1928-1930 in the Denver shops. All

of the K-37s had the box type tender, and not the Vandy one that

I modeled. All of the C-41's with the Vandy tender were

scrapped. I still thought it would be neat to see the engines

side by side and compare them. Again, all I had for a plan for

the engine is the two pictures at left, and an O scale model of

the D&RGW's C-48 2-8-0,

so I may be a little off on my dimensions. As you can see, the

K-37 has a longer smoke box and a smaller cab than the C-41. The

reason for this is when the D&RGW lowered the C-41 boiler onto

the K-37's NG 2-8-2 chassis from Baldwin, the boiler had to be

moved back in order for the firebox to clear the rear set

of drivers (I had always wondered why I had so much cab swing on

the K-36 / K-37 class engines around my own curves!). Of course

the smoke box also had to be lengthened to fit the chassis, thus

the K-37 NG engine is longer the C-41 SG engine! From what I can

tell, the only thing that the Grande used from the C-41 was just

the boiler only, and fabricated everything else in the shop,

like the cab, rear frame extension, smoke box, etc. What a kit

bash. I had always wondered why the brass importers never

offered a model of the C-41 at the same time they made ones of

the K-37. Well, I understand now. It is almost a totally new

project! It has been a fun venture, but has it has had its

moments with no real plan to work from. My best work comes from

having an O scale model, 1:22.5 scale plans, and many pictures

from which to work from. This project had few. You decide if the

C-41 is on the money or not--I won't be offended if you think

not. I hope to do an article on the conversion some time, but

for now enjoy what I have come up. As

most of you know, the K-37 NG engines were built from the C-41

SG engines by the Grande in 1928-1930 in the Denver shops. All

of the K-37s had the box type tender, and not the Vandy one that

I modeled. All of the C-41's with the Vandy tender were

scrapped. I still thought it would be neat to see the engines

side by side and compare them. Again, all I had for a plan for

the engine is the two pictures at left, and an O scale model of

the D&RGW's C-48 2-8-0,

so I may be a little off on my dimensions. As you can see, the

K-37 has a longer smoke box and a smaller cab than the C-41. The

reason for this is when the D&RGW lowered the C-41 boiler onto

the K-37's NG 2-8-2 chassis from Baldwin, the boiler had to be

moved back in order for the firebox to clear the rear set

of drivers (I had always wondered why I had so much cab swing on

the K-36 / K-37 class engines around my own curves!). Of course

the smoke box also had to be lengthened to fit the chassis, thus

the K-37 NG engine is longer the C-41 SG engine! From what I can

tell, the only thing that the Grande used from the C-41 was just

the boiler only, and fabricated everything else in the shop,

like the cab, rear frame extension, smoke box, etc. What a kit

bash. I had always wondered why the brass importers never

offered a model of the C-41 at the same time they made ones of

the K-37. Well, I understand now. It is almost a totally new

project! It has been a fun venture, but has it has had its

moments with no real plan to work from. My best work comes from

having an O scale model, 1:22.5 scale plans, and many pictures

from which to work from. This project had few. You decide if the

C-41 is on the money or not--I won't be offended if you think

not. I hope to do an article on the conversion some time, but

for now enjoy what I have come up.

|

|

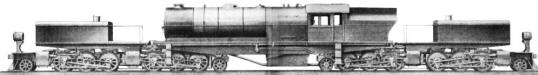

D&RGW

L-131 2-8-8-2 D&RGW

L-131 2-8-8-2

(2007-2008)

Built by Alco in 1927, the L-131

2-8-8-2 was the D&RGW's largest and most powerful class of steam

locomotive, measuring 120 feet long from pilot to tender, 11'-8"

wide, and 16'-1½" tall; and boasting 131,800 lbs. of tractive

effort from its 63” drivers. Each tender carried 30 tons coal and

18,000 gallons of water. Walschaert valve gear was original

equipment on both the 3600-3609 series L-131, and the 3610-3619

series L-132 built a few years later in 1930. Like all D&RGW standard

gauge steam, save for a lowly slide valve C-28 2-8-0 of 19th century

vintage, the L-131s were retired and scraped, mainly over the period

1955-1956, having been replaced by FTs initially and then other EMD

"covered wagon" first generation diesels.

Barry's 1:22.5 scale, Gauge 3 model is powered by modified LGB

Mikado drive units using custom made white bronze drivers, but with

LGB wheels on all other axles. When complete, the engine and tender

will measure 64” long and be capable of negotiating a 5' foot

minimum radius curve. A Digitrax decoder and Phoenix 2K2 sound will

be mounted in the tender. |

|

The Tender

|

|

The Chassis & Drivers

One

of the first issues for Barry to settle in planning the construction

of the Gauge 3 L-131 2-8-8-2 was where to find suitable drivers.

Nothing in the usual LGB or other Gauge 1 product lines even

remotely approached the large 2.8" diameter spoked drivers he would

need, that is, with one exception. The drivers for Barry's L-131

do have an LGB origin of sorts: Several years ago, LGB

commissioned Aster of Japan to build a series of limited production

NYC J1e 4-6-4s in Gauge 1. Barry was able to acquire several spare

drivers from one of these locos and to modify its center from a

boxpok to a spoked configuration. With the addition of crankpins,

Barry's modified driver became a casting pattern. Yet another Texan,

Dennis Mashburn (of K & D

Castings) produced white bronze investment castings from Barry's

master and then machined the tread on each of the drivers. Barry did

not use separate tyres on these drivers; rather, insulation is

accomplished using a delrin bushing on the shouldered end of each

6mm Gauge 3 axle. The end of each axle is knurled, the bushings are

themselves machined for a .001" on the radius interference fit, and

then the bushings have red

Loctite applied to them before

being pressed into each driver. One

of the first issues for Barry to settle in planning the construction

of the Gauge 3 L-131 2-8-8-2 was where to find suitable drivers.

Nothing in the usual LGB or other Gauge 1 product lines even

remotely approached the large 2.8" diameter spoked drivers he would

need, that is, with one exception. The drivers for Barry's L-131

do have an LGB origin of sorts: Several years ago, LGB

commissioned Aster of Japan to build a series of limited production

NYC J1e 4-6-4s in Gauge 1. Barry was able to acquire several spare

drivers from one of these locos and to modify its center from a

boxpok to a spoked configuration. With the addition of crankpins,

Barry's modified driver became a casting pattern. Yet another Texan,

Dennis Mashburn (of K & D

Castings) produced white bronze investment castings from Barry's

master and then machined the tread on each of the drivers. Barry did

not use separate tyres on these drivers; rather, insulation is

accomplished using a delrin bushing on the shouldered end of each

6mm Gauge 3 axle. The end of each axle is knurled, the bushings are

themselves machined for a .001" on the radius interference fit, and

then the bushings have red

Loctite applied to them before

being pressed into each driver.

For

the mechanism of the L-131, Barry is using two regauged LGB Mikado

motor blocks which have themselves been extensively modified with

respect to their wheelbase. With a hinge in each motor block, and

then two motor blocks per locomotive which are themselves mounted

independent of each other, though slung beneath one boiler, Barry is

in effect building in mini- For

the mechanism of the L-131, Barry is using two regauged LGB Mikado

motor blocks which have themselves been extensively modified with

respect to their wheelbase. With a hinge in each motor block, and

then two motor blocks per locomotive which are themselves mounted

independent of each other, though slung beneath one boiler, Barry is

in effect building in mini- ature the proposed Beyer Peacock Quadruplex 2-6-6-2+2-6-6-2 (or "Super Garratt" is it has sometimes

been called) that was seriously offered by Beyer-Peacock in 1927.

Barry describes the conversion process in his own words: ature the proposed Beyer Peacock Quadruplex 2-6-6-2+2-6-6-2 (or "Super Garratt" is it has sometimes

been called) that was seriously offered by Beyer-Peacock in 1927.

Barry describes the conversion process in his own words:

"It

was time to slice into the LGB Mikado motor block to lengthen it to

accept the larger L131 drivers. I milled out some 1/4 X 3/4 plastic

bar stock for the main frames to hold the drivers at the correct

spacing. I then cut the motor block in four places to stretch it

out. Next, I glued both main frames to the side of the motor end of

the motor block. I then glued the short sections of the second and

third driver axles, to the main frames. The hinge section was

attached together and glued into the frame assembly, and last I

added the other end between the main frames. I added spacers to keep

the axles centered, and lengthened the drive tube between the two

worm gears. I had to move the electrical pick ups from the original

location, to meet the new wheels. New wiring wrapped up the loose

ends and got the motor some power. It ran on the straight track of

the test track OK, but the layout will tell the truth. I cut both

sides of the main frame next, on both sides and this allows the

motor block to flex on the curves and turnouts. After a few

adjustments with the wheel gauge and the hinge gap, it ran great.

This is the start of the front engine. Hope to get the rear engine

up to this point soon. The pictures above and below show the original block next to

the modified one, just for reference."

|

|

The Boiler &

Cab

The boiler on the

L-131 is a large, 4" diameter length of PVC pipe with a styrene

spacers and a sleeve of styrene sheet added to their circumference

to match the dimensions and taper of the prototype's boiler jacket.

Barry writes,

"The L131 is just big, so big that it is hard

to handle. This will be the first engine that I do not have to

add a metal weight to. Don't ask me how much it weighs, but it

is heavy. the boiler is over a half inch thick at the largest

point. The first pictures show the pipe attached to the engines

on the layout, before I added the taper to it. Later pictures

show how I added the strips to build it up and add the 40 thou

thick jacket sheet to it. I then turned the boiler upside down

and filled it with urethane, to make it solid between the pipe

and the outside 40 thou jacket. The basic boiler is done and the

running boards are going on next, followed by a bunch of foo foo

to make it look good. I added the sound speaker in the fire box

area, so sound will come from the engine, instead of the tender.

I may add an additional speaker in the smoke box area, if I

think it needs it. It has really been a fun project to work on,

and I would like to have it done for the Lone Star Regional

convention here in town, in the middle of June. We will see."

"I brought the engine up to the layout to test the distance from

the tender and engine, as well as check the clearances around

the curves. I thought I would have to do some major revisions to

the scenery, but in only two places do I have to make changes,

to accommodate the cab swing. I was worried about the pivot

points from the engines to the boiler, but they are in the

correct places to clear most all the scenery. Over all, I am

please with how it runs and that I don't have to go back and

make corrections. I am glad this is not my first engine to

build! The hardest part of this engine project is handling it,

or turning it around on the workbench. It is very heavy and

long. I am not sure how I am going to hold the boiler to paint

it."

The photos below were taken in

April and May of 2008:

The Completed Locomotive

Without paint . . .(notice the narrow

gauge C-16 in the foreground!)

Barry has this to say about the end of

the project:

|

"The BLW shop crew has been very busy and

finally got the L131 out the door and ready for the paint

shop. All the foo foo is just about on it now and they have

decided to call it a "Choo Choo". It is the largest piece of

rolling stock that I have built, at 65 inches coupler to

coupler, 9 inches high and 6 inches wide. Of course it runs

on my five foot radius track and looks funny doing it, but

hey, it's what I wanted. I have a little more work to do on

the engines once I remove them from the boiler, and ready it

for wiring and sound. The engine is very heavy and I don't

always know where to lift it from. I will be glad when it is

on the layout to stay. Over all, I am pleased with how it

turned out. There were very few revisions to get it to run

and all the planning and homework paid off. Would I build

something this large again? Well..... yes from the fact

that I really enjoy large locomotives, no from the fact it

is so hard to handle and it takes up so much space. (I would

probably say yes, if you really want to know)"

"I want to say a big thanks to all who have helped me with

this project. Dave Brown for all the great pictures of his

PSC L132 O scale engine, Mark Gardner for the plans from the

Colorado Railroad Museum and the pictures of his PSC L131 O

scale engine, Craig Brantley for loaning me his O scale Max

Gray L131 engine and reducing the plans for me, Ward Hammond

for all the laser work, James Engle for the custom decals,

yet to go on, Jonathan Meador at LGB of America for help

with all the drive parts, and Dennis and Kathy Mashburn who

cast all the drivers and Dennis who machined the centers for

me.Without help from good friends, I

would not be able to build what I do. Thanks Guys!"

"I was asked what I will do to top this project? Well, nothing

soon, but I like large engines and a Big Boy has always been

a favorite of mine." |

Painted and lettered . . .(And in the

last set of frames at the 2008 Lone Star NMRA Convention)

|

|

Last update: 20 January 2009

|